In an era of visual ubiquity and near-image overload, “being collected” means transforming ephemeral moments into a history that can be examined and narrated. As Asia’s photography ecology matures, both public and private collections not only shoulder the responsibility of preserving visual memory but are also responding to profound shifts in how images are created, disseminated, and understood.

On May 29, 2025, the Seoul Museum of Photography (Photo SeMA), after a full decade of preparation, officially opened to the public. As South Korea’s first public art institution dedicated to photography, its establishment not only provides photography enthusiasts with a new public gathering and exchange space but also marks an institutional attempt: through systematic collection, curation, and research, to reconstruct the overlooked, fragmented, and even unwritten history of Korean photography.

© PhotoSeMA. Installation view of "Storage Story", photos by Image Zoom. Courtesy of PhotoSeMA.

© PhotoSeMA. Installation view of "The Radiance: Beginnings of Korean Art Photography", photos by Youngdon Jung. Courtesy of PhotoSeMA.

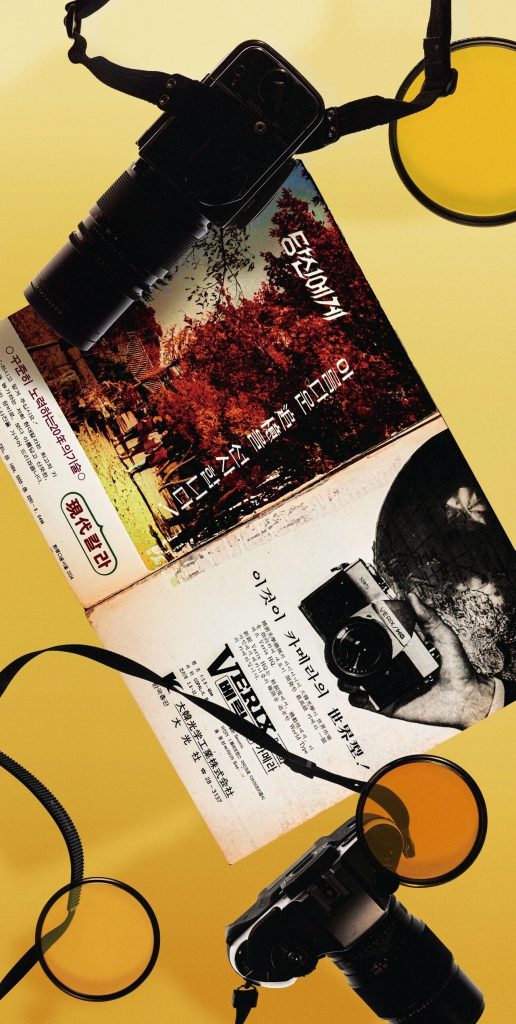

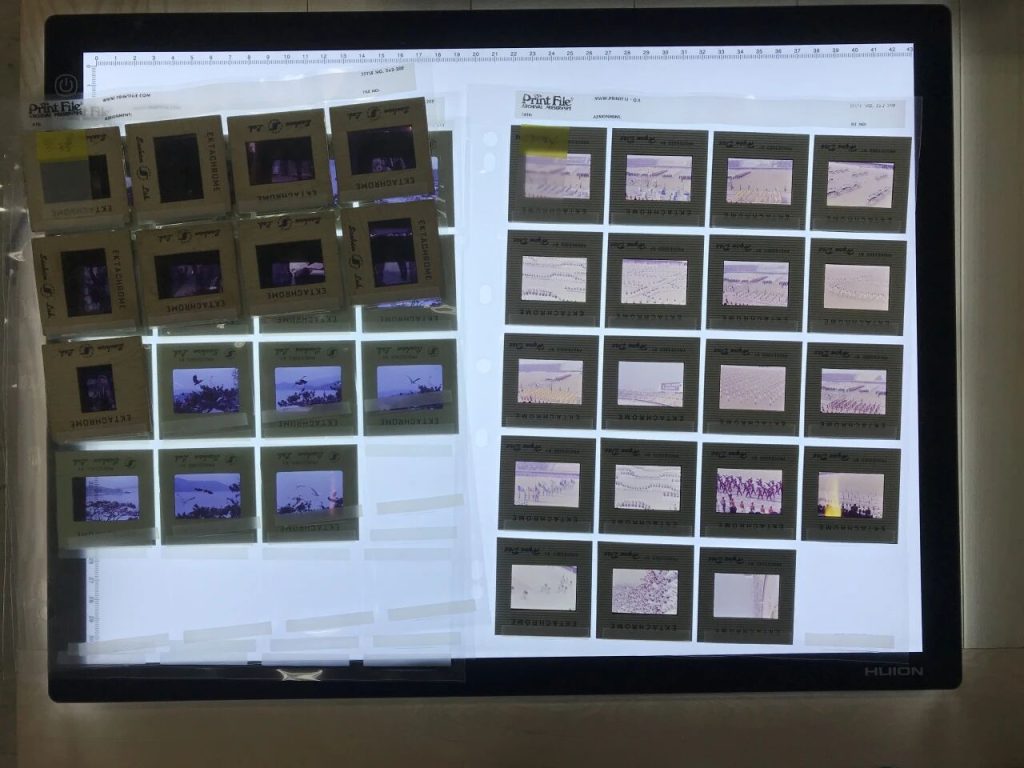

Photo SeMA’s inaugural exhibition, THE RADIANCE: BEGINNINGS OF KOREAN ART PHOTOGRAPHY, focuses on a select few key figures to illustrate how photography gradually evolved from a documentary tool to being recognized as “art.” During its preparatory phase, the museum prioritized sorting and acquiring 20,000 archival items and works from the 1920s to the 1980s, covering various forms such as documentary photography, artistic creations, commercial portraiture, as well as negatives, cameras, and publications.

Institutional collecting is never a passive process of accepting objects; it is an ongoing system of value judgment: what to collect, how to categorize, and how to narrate and present them directly impact the “visibility” of history. Recently, we had the privilege of speaking with the curator (Hyunjung Son) of Photo SeMA, listening to her thoughts on institutional collecting, the positioning of Korean photography, and future possibilities.

INTERVIEW

Q: The Photography Seoul Museum of Art is the first public museum in Korea dedicated to photography. Why did you choose “photography” as the museum’s focus? Could you share the inspiration behind its establishment? Does this reflect a particular statement about the unique nature of this media?

A: The Photography Seoul Museum of Art (Photo SeMA) is one of the Seoul Museum of Art’s genre-specialized branches, and its focus on photography responds to a significant institutional and cultural gap in Korea. Until now, Korea lacked a public museum solely dedicated to photography. While the DongGang Museum of Photography in Gangwon-do has long played a valuable role, its regional location posed accessibility limitations—especially for those in Seoul and other metropolitan areas.

Historically, photography-focused spaces in Seoul were largely led by private institutions, and within comprehensive art museums, photography often remained on the periphery due to the lack of dedicated curators and resources. Despite this, Korea is one of the most photography-saturated societies in the world. With the country’s high smartphone penetration and camera usage, nearly everyone is constantly producing and engaging with photographic images. There has been an unmistakable public hunger for photographic expression—across generations and contexts.

This uniquely Korean condition underscored the urgent need for a public institution that could research, archive, and present photography both as a historical and evolving medium. The establishment of Photo SeMA is both a cultural response and an institutional commitment: it aims to support serious scholarship on Korean photographic history, preserve the material legacies of photographers, and explore contemporary shifts in image-making in a rapidly transforming media environment. In this sense, our focus on photography is not simply about filling a gap—it’s a statement on the medium’s profound relevance to our visual culture today and its unique power to mediate memory, identity, and change.

Q: From conception to opening, what was the biggest challenge you and the museum team faced? Were there any particularly moving or unexpected moments along the way?

A: In truth, it took nearly ten years from the project’s start to the museum’s opening. The initiative began in 2015, and I joined the process in 2016. Back then, there was only one staff member dedicated to the museum. Today, we have a team of fifteen sharing this space—each with different roles, but working together under the same vision.

The biggest challenge was uncertainty. For a long time, we kept asking ourselves, “Will this museum truly come to life?” As with many public projects, the future often felt unclear. But a month after opening, I looked around and realized that Photo SeMA was no longer just one idea or one space—it had started to branch out and become many things to many people. That quiet shift, from uncertainty to shared meaning, was deeply moving.

© Photography Seoul Museum of Art. The Advisory Committee (the 7th meeting)

© Photography Seoul Museum of Art, Photo_ GENIEPROJECT. A Place for Photography (photo by GENIEPROJECT)

Q: The inaugural exhibition, “The Radiance: Beginnings of Korean Art Photography”, focuses on five pivotal figures in Korean photographic history rather than a broader survey of artists. What was the reasoning behind this curatorial approach? Could you elaborate on the significance of these five photographers in shaping Korea’s photographic art?

A: In preparing for the museum’s opening, we acquired the works of 26 photographers, and among them, selected five key figures to illustrate defining turning points in the history of Korean art photography. Rather than offering a broad survey, we wanted to spotlight specific artists whose practices mark crucial moments in how photography evolved into a recognized art form in Korea.

The Radiance explores photography’s journey from a documentary tool to a medium of aesthetic, social, and conceptual inquiry. Revisiting the legacies of these five artists allows us not only to trace that transformation but to pose new questions about how we engage with photography today.

- Jung Haechang held Korea’s first solo photo exhibition in 1929. He pioneered the integration of Western formalism and Korean aesthetics, opening experimental possibilities through still life and narrative-based photography.

- Lee Hyungrok shaped post-war realism, documenting ordinary lives while blending modernist structures and social engagement. His dual approach bridged documentary urgency with formal innovation.

- Lim Suk Je offered a critical realist vision after Korean liberation, capturing workers with dignity and depth. His prints conveyed solidarity and subtly powerful narratives, establishing new standards for photographic expression.

- Cho Hyundu advanced abstract photography in the 1960s, expanding the medium beyond representation into pure visual language. His achievements showed that Korean modernist photography had its own strong experimental lineage.

- Park Youngsook brought a feminist gaze to photography. Her early works from the 1950s–60s, recently rediscovered during our research, quietly traced women’s inner worlds—laying the groundwork for later feminist discourse in Korean photography.

By centering these five, we aimed to present not just history, but a constellation of sensibilities that continue to resonate in today’s photographic practices.

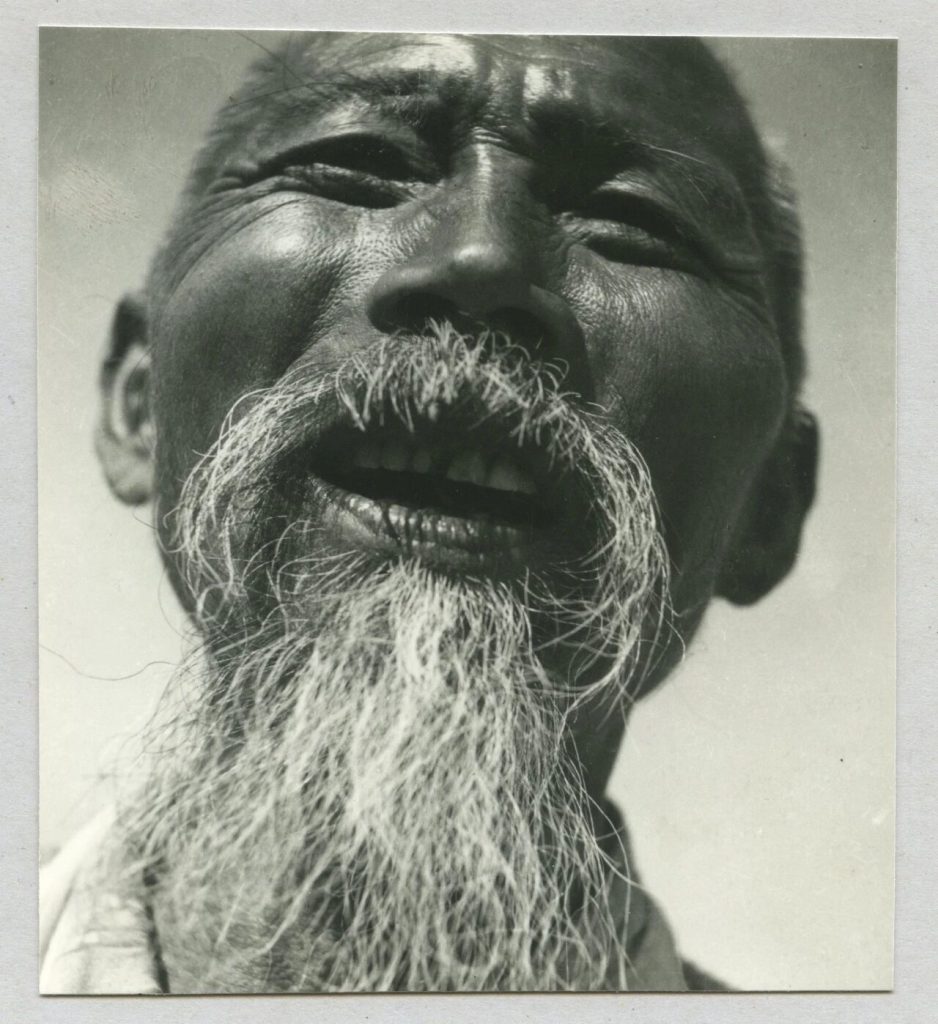

©Lim Suk Je, Old farmer, 1946, gelatin silver print, 11.2×10cm, Collection of Photography Seoul Museum of Art

©Lee Hyungrok, Composition, 1956, gelatin silver print, 24.46×17.62cm, Collection of Photography Seoul Museum of Art

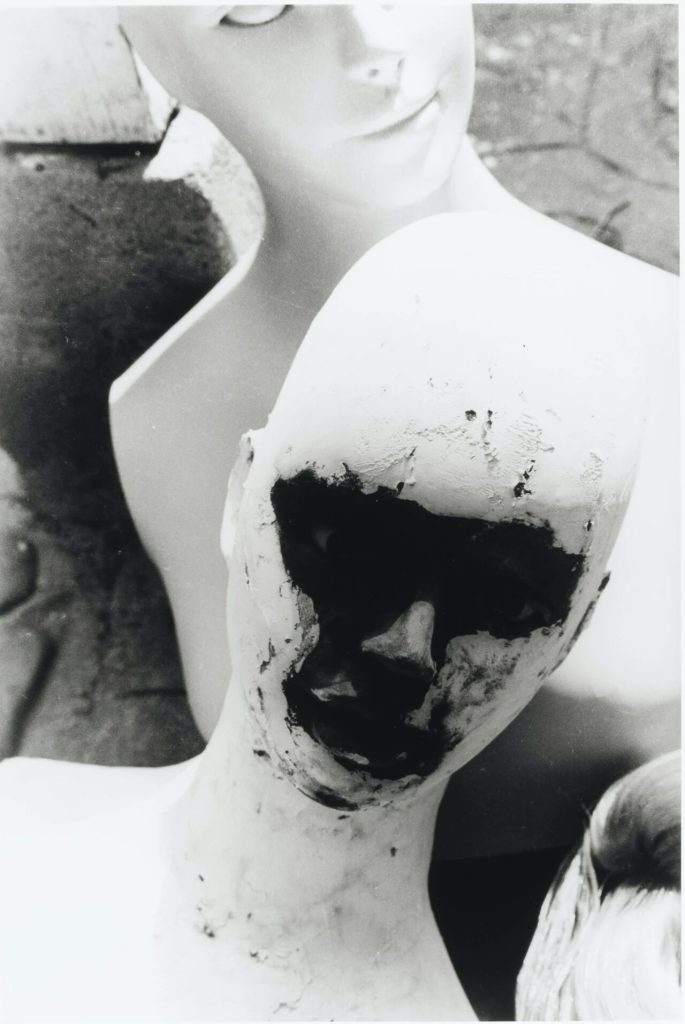

©Park Youngsook, NEW MASK, 1963/2021, gelatin silver print, 44ⅹ29.8cm, Collection of Photography Seoul Museum of Art

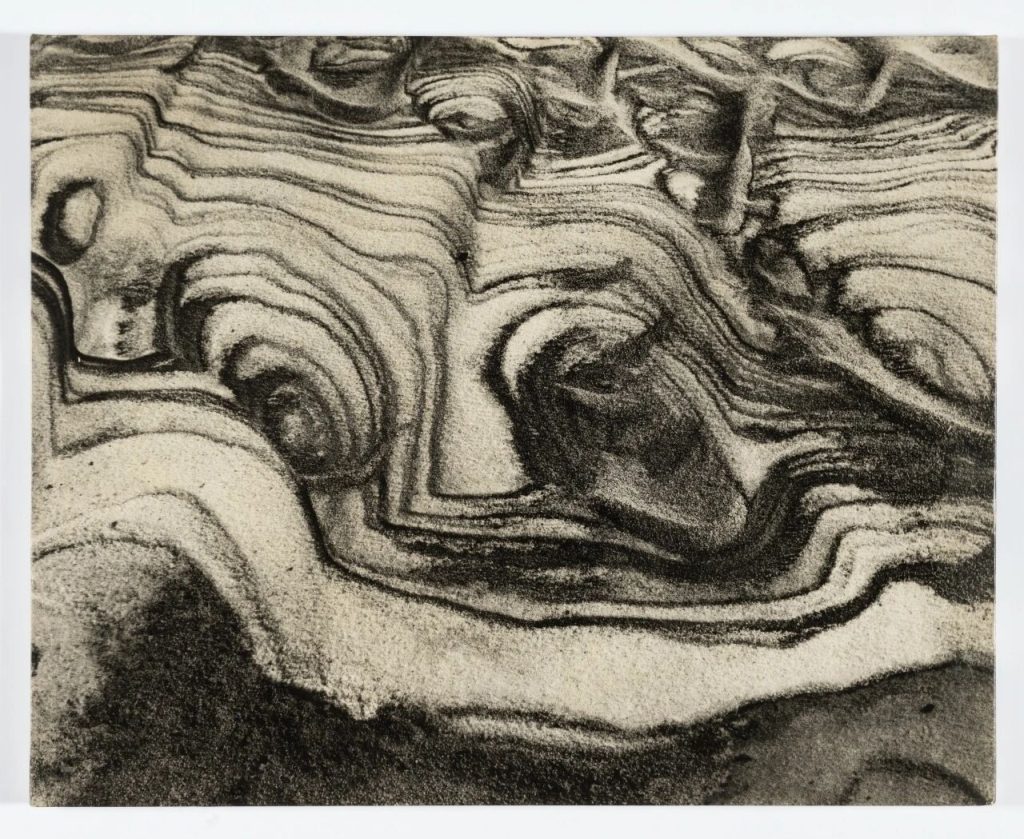

©Cho Hyundu, Lingering snow, 1966, gelatin silver print, 65.6×82.2cm, Collection of Photography Seoul Museum of Art

©Jung Haechang, no title, unknown date, gelatin silver print, 11.1×15.5cm, Collection of Photography Seoul Museum of Art

Q: We’ve heard that this exhibition involved extensive research and archival work before reaching the public. What stood out most during this process? What discoveries emerged while tracing the evolution of Korean photography, and did they alter your perspective on it?

A: To establish a more objective foundation for Korean photographic history, we conducted a large-scale, three-year research project. We compiled data spanning roughly a century—from the 1880s to the 1980s—examining exhibitions, publications, key articles, and events related to photography in Korea. This process revealed the names of over 20,000 photographers. Based on recurring mentions and contextual weight, we identified 200 significant artists as top-priority figures for collection.

We also analyzed the collections of SeMA and other key institutions across Korea to understand what narratives had been emphasized—and, more importantly, what had been overlooked. Rather than acquiring more editions of already canonized works, we focused on filling in the gaps: rediscovering underrepresented artists and previously invisible threads in Korean photographic history.

What surprised us most was how interconnected these photographers were—across generations, regions, and practices—despite how much our current understanding centers around a few prominent figures. This research reshaped our approach: instead of reinforcing a narrow canon, we’ve begun to expand the frame, to reflect the plural voices that have shaped Korean photography.

Q: Beyond “The Radiance”, the museum has also organized “Storage Story”, featuring six emerging artists whose works reflect the museum’s construction and its connection to the surrounding area. What was the curatorial vision behind this exhibition?

A: Storage Story was curated by my colleague, Sojin Park, and developed over the course of a year through commissions with six emerging Korean photographers. The exhibition reimagines the museum’s formation not as a purely bureaucratic or architectural event, but as a layered, sensory, and interpretive site.

Drawing from the museum’s location in Chang-dong (literally meaning “warehouse district”), the exhibition explores the evolving concept of “storage”―from a physical grain depot to an image archive, repository of memory, and site of digital and ecological data. It questions how photography, often seen as a tool for documentation, can instead function as a medium of reflection, construction, and reimagination.

Each artist engaged with different facets of the museum’s material and symbolic construction—its site, archives, ecosystem, and community. In doing so, the exhibition positions the museum not as a finished institution, but as a collective and ongoing act shaped by technology, memory, and transformation. It also opens up broader questions around the ontology of photography—what it is, what it holds, and how it might continue to evolve within contemporary art.

Dongsin Seo, Continuous and Stable, 2025, Archival pigment print, 100×133cm

©Oh Jooyoung, Aura Restoration Index 1, 2025, Photographs of collection items, network analysis index of collections, Variable installation

©Joo Yongseong, Guardian Jar for Lord Yi Yoo of Nokcheon, Chang-dong Note, 2025, Pigment print, 105×140cm

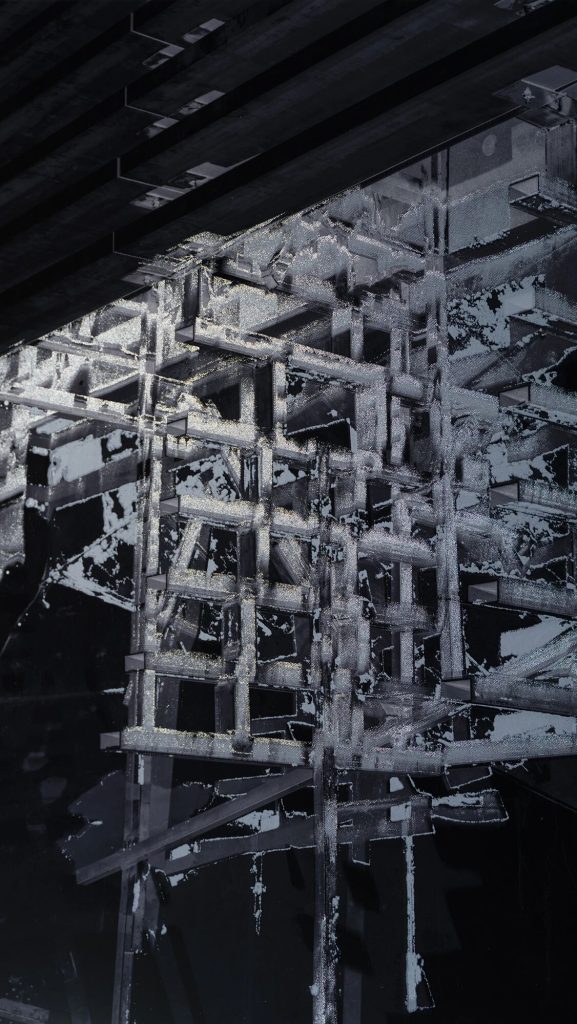

©Won Seoung Won, Unfinished Architecture, Nature in Construction, 2025, Archival pigment print, 269×149cm

©Melmel Chung, A Vault Without Walls: Unframed, 2025, Inkjet print on flex fabric, mounted on lightbox, 120×240×17cm

©Jihyun Jung, Cast Capture_SP#02-4622, 2025, Silkscreen on pigment print, 94×167cm

Q: In your opinion, what are the defining aesthetic characteristics and thematic concerns of the new generation of Korean photographers? Could you recommend three rising Korean photographic artists we should pay attention to?

A: I’d like to highlight three artists in particular: Seo Dongshin(https://dongsinseo.com/), whose work is currently featured in Storage Story and engages deeply with questions of space and memory; Yang Seungwon(https://www.instagram.com/iso_yg/), an emerging photographer actively exploring the visual language of contemporary Korea; and Kim Hyoyoun(http://hyoyeon-kim.com/), who takes a documentary approach to capturing historical narratives with striking clarity and emotional depth.

Each of these artists reflects a different facet of photographic practice today—conceptual, aesthetic, and archival—and together, they represent the dynamic range of voices shaping Korea’s photographic landscape.

Q: From the point of view of the institution, how do you define the role of an art collection? Could you briefly share the current state of the Photo SeMA’s collection, such as the collection numbers, the range of artists represented, and categorization, etc.? What is the most precious or unique piece in the collection, and is there a notable story behind its acquisition?

A: I believe that an institution’s identity is ultimately defined by its collection. During the establishment of Photo SeMA, we conducted five rounds of acquisitions and gathered over 20,000 works and archival materials by 26 artists. These span a wide spectrum—from documentary and fine art to commercial photography, portraiture, and even photographic cultural artifacts such as books, film canisters, cameras, and ephemera. Importantly, since Photo SeMA is a branch of the Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA), our holdings are part of the larger SeMA collection. While the main museum had focused primarily on contemporary photography from the 1990s onward (with 1,251 works), we concentrated on filling the significant historical gap prior to that period—especially from the 1920s to the 1980s.

One particularly memorable acquisition was the archive of commercial photographer Jung Heeseub, who was active from the 1950s to the 1970s. His remaining negatives were carefully stored in a repurposed metal ammunition canister, likely dating back to the Korean War. I vividly remember the unexpected weight and metallic smell of the container—it sharply contrasted with the lightness of the film it held. When we scanned the negatives, we discovered serene and surprisingly romantic portraits of couples posing in natural landscapes. The poetic intimacy of these images, set against the harsh materiality of the canister, left a lasting impression. It was a moment that reminded us how photography holds not only visual memory, but also the traces of history, labor, and tenderness—sometimes hidden in the most unexpected containers.

© Photography Seoul Museum of Art. At the temporary storage.

© Photography Seoul Museum of Art. At the temporary storage

Q: Will the museum prioritize documentary photography from Korea’s transitional periods or experimental image-based art? How do you balance the two? What are the future plans for the museum’s photographic acquisitions?

A: At Photo SeMA, our focus is on strengthening the museum’s role as a collector of photographic materials—negatives, prints, ephemera, and archives—while the acquisition of artworks is integrated with SeMA’s broader collection policy.

Rather than emphasizing a specific era or genre, we plan to develop our collection through annual thematic focuses and curator-driven proposals. This approach allows us to balance historical and contemporary works organically, responding to shifting discourses in the field.

Currently, we are working to deepen our holdings in both modern and contemporary Korean photography, while also beginning to prepare for the acquisition of international works. Our goal is to reflect the complexity of photographic practice—across timelines, geographies, and visual strategies—and to create a collection that speaks both to Korea’s unique photographic history and to global conversations on the image today.

Q: In recent years, Asian themes have gained significant traction in the international contemporary art scene, with a new wave of Asian photographers stepping onto global platforms. How do you interpret this trend? Amid today’s shifting global dynamics, what opportunities and challenges do Korean and Asian artists face?

A: It’s encouraging to see growing international interest in Asian perspectives within contemporary photography. However, I approach this trend with both curiosity and caution. While increased visibility offers long-overdue recognition, we must also ask: On whose terms are these narratives being framed? And what kinds of images are expected from “Asia” in global contexts?

For Korean and other Asian artists, the opportunity lies in expanding authorship—shaping their own discourses, aesthetics, and histories beyond Western frameworks. At the same time, the challenge is to resist being reduced to cultural representatives or visual proxies for geopolitical shifts.

Ultimately, I believe this moment invites us to think critically about visibility: not just who is seen, but how and why. As curators, we also carry the responsibility to cultivate platforms where diverse practices from Asia are presented with complexity, agency, and nuance—not as trends, but as evolving, self-defined narratives.

© Photography Seoul Museum of Art. The Advisory Committee (the 1st meeting)

© Photography Seoul Museum of Art. The Advisory Committee (the 7th meeting)

© Photography Seoul Museum of Art. The Advisory Committe (dismissal ceremony)

Q: Five years from now, how would you like the public to perceive this museum? What upcoming exhibitions and research initiatives are planned? Are there intentions to spotlight underrepresented creators, such as women artists? Does the museum plan to collaborate with international art institutions/organizations to further discourse on contemporary image-making?

A: As outlined in the museum’s founding statements and recent press materials, Photo SeMA positions itself as Korea’s first public art museum entirely dedicated to photographic media. Its long-term vision is to become a cultural platform that fosters diverse dialogues around photography—historical, experimental, and interdisciplinary.

The museum aims to highlight the power and artistic value of photography, support critical research on Korean photographic history, and promote active exchanges between artists, curators, and institutions both in Korea and abroad. According to public materials, there are ongoing plans for year-round exhibitions, archival research, and educational programs that include a focus on underrepresented voices—such as women artists—and historically overlooked practices.

International collaboration is also presented as a key element of the museum’s strategy. Rather than simply presenting Korean photography to the world, the museum seeks to build reciprocal relationships that situate Korean image-making within broader global conversations on contemporary visual culture.