Li Shun, born in 1988 in Xuzhou, Jiangsu Province, received his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from the School of Intermedia Art, China Academy of Art (CAA), and now lives and works in Hangzhou. In April 2023, Li Shun made a significant impact with his debut at the 8th edition of PHOTOFAIRS Shanghai. His featured works interprets traditional calligraphy through the lens of photography, immediately captivating attention from collectors, media, and the public.

Li Shun

What makes Li Shun fascinating is not only the intricacies of his creative process but also his pushing of photography’s boundaries—a journey consistently anchored in contemporary cultural context. For Lishun, light and shadow serve not only as inspiration but also as sources to delve into more diversified expressions. His works encompass translations, transcripts, images, texts, and concepts. This complex interplay shapes a distinctive style that speaks to both history and reality.

Li Shun’s first solo exhibition at Ginkgo Space (Shanghai), titled Stream of Ideas in Mountains and Seas, runs until the end of December. In this exhibition, Li Shun shares his unique insights into the universe and history through the portrayal of landscapes. Notably, his adept use of modern tools, such as cameras, lighting and computers, redefines the conventional notion of brushstrokes in Chinese ink painting. As the artist embarks on a new chapter in his creative journey, we had the opportunity to talk to him.

© Exhibition View of Stream of Ideas in Mountains and Seas, 2023. Courtesy of Ginkgo Space

PF: Could you explain the creative process behind your recent work, Remnant Mountains?

Li Shun: Remnant Mountains is an extension of my exploration creating words with light. My solo exhibition, Capture the Light and Shadow, was held at the Zhejiang Art Museum in March, 2023. This exhibition offered a comprehensive review of my light series, a body of work that has developed over 13 years, spanning from 2009 to 2022.

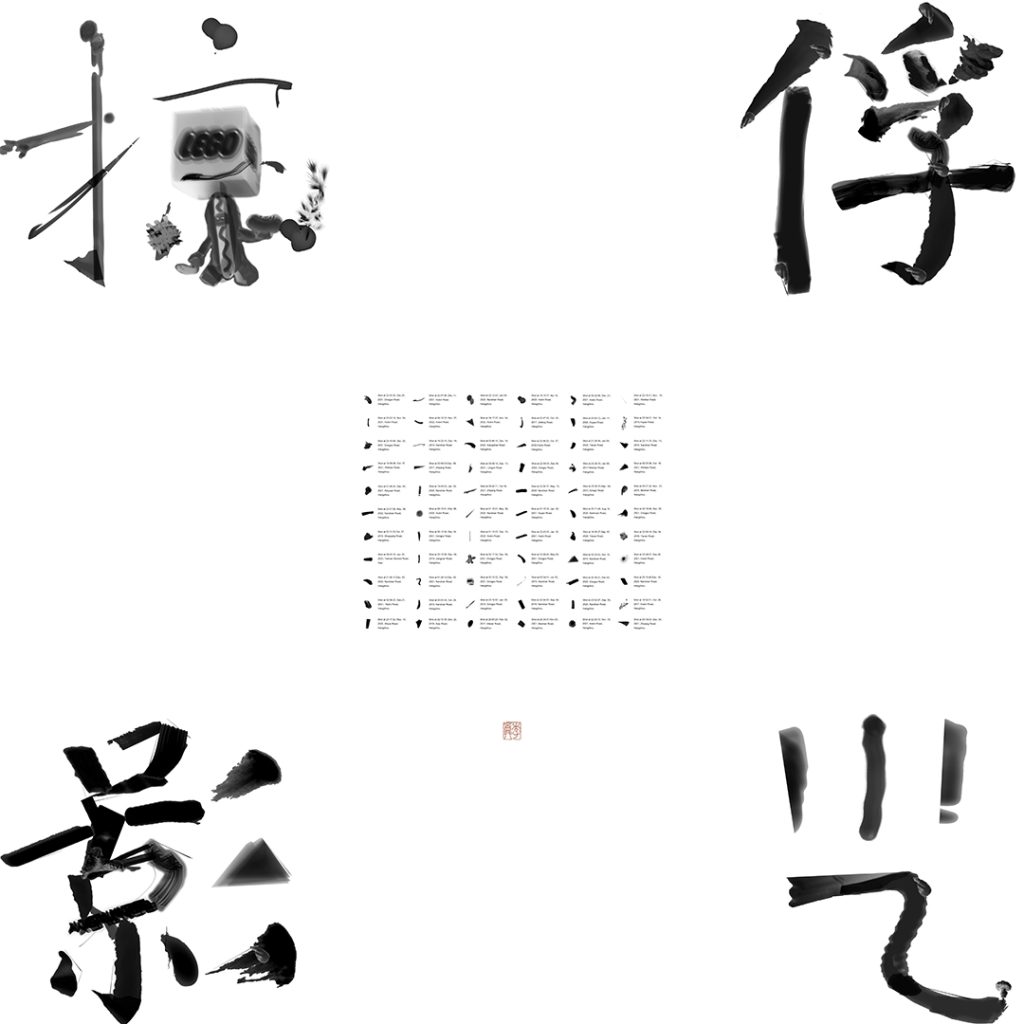

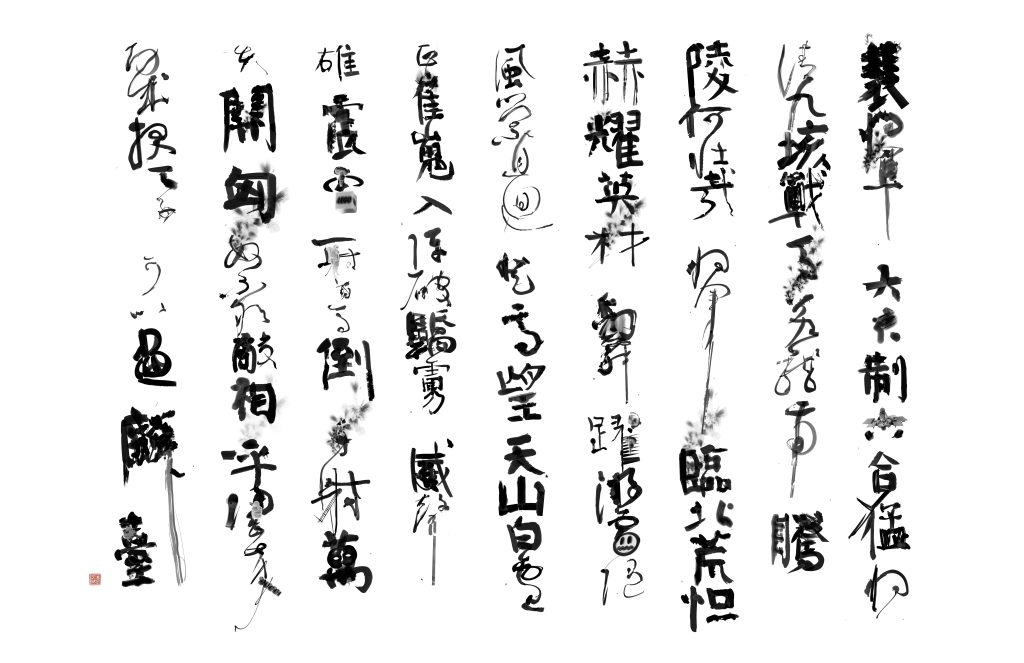

It was during a black-and-white film photography class at the China Academy of Art in 2009 that I started to collect light and shadow images. Over time, this collection evolved into a vast database containing hundreds of thousands of light and shadow materials. As the quantity expanded, so did the quality of my exploration. Initially, I was drawn to the various trails of light cast by city lights. Those images naturally evoke thoughts of traditional Chinese calligraphy, particularly the strokes in cursive scripts. As I organized my growing database, I started to classify large blocks of light and shadow after categorizing dots and strokes. Those blocks make me think of the various texture stroke techniques in traditional Chinese landscape painting. My creative process remains consistent—I record the nocturnal cityscape and transform fleeting light into brushstrokes. Therefore, all the brushstrokes in my artwork are, in essence, the trajectories of skyscrapers and the traffic captured through long exposures.

© Li Shun, Study on the Nature of Things- Remnant Mountain, Photography, Printed on Rice Paper, 117.5×231.5cm, 3+1AP, 2023.

PF: Did you break any new ground when shifting from creating words with light to painting with light? Did this process bring a fresh perspective on photography for you?

Li Shun: All the fresh creative endeavors are quite personal. I’m trying to explore and present a more diverse artistic language and form, all of which are my attempts in this phase. As you know, creation is like crossing the river by feeling the stones, sometimes involving trial and error. You might just discover the right answer at the end of a wrong path. I’ve been particularly interested in the notion of ‘Shanshui’ (which translates as landscape) in traditional Chinese art. Therefore, my goal is to offer a fresh interpretation of contemporary landscape views. Photography, with its capacity to capture both the concrete and the abstract, is merely a form—a tool for expression.

PF: In traditional painting, brushstrokes represent a delicate blend of technique and spirit. In your artistic endeavors, the lens, the interplay of light and time, and computer post-processing have evolved into a novel kind of brushstroke. Could you shed light on how you interpret the concept of brushstrokes, particularly the innovative approach in your works?

Li Shun: I believe brushstrokes should evolve with the times—each era’s ideology determines its artistic forms. Much of my work is a reflection on the current state of traditional Chinese literati art. Take calligraphy for instance, traditional literati art that has, to a large extent, lost its foothold in our contemporary environment. The language systems, media traditions, interpersonal relationships, and cultural atmosphere that once supported this art have all but disappeared. When I create words with light, it isn’t a complete deconstruction of calligraphy. Instead, I utilize photography, a contemporary medium, to instigate a fresh reconsideration of it. In this process, what I do is not to discard or abandon, but rather to find a fit in the present era, thereby proposing a new possibility.

© Li Shun, Study on the Nature of Things - Capture the Light and Shadow, Photography, Printed on Rice Paper, 99×99cm, 6+1AP, 2023.

© Li Shun, Study on the Nature of Things - Capture the Light and Shadow (detail), 2023.

PF: In your opinion, what are the differences and connections between the “replication” in photography and the “imitation” seen in painting?

Li Shun: I always think that ever since the invention of photography in 1839, it has rescued painting from the task of “imitating” the world, allowing painting to return to its essence. Photography leans towards recording, while painting is about expression, and rubbing can be viewed as a blend of replication and inheritance. Ultimately, they all serve as tools and languages.

© Li Shun, The Light from the Sea, Photography, Barium Sulfide Photographic Giclee Print, 66.5×100cm, 6+1AP, 2017.

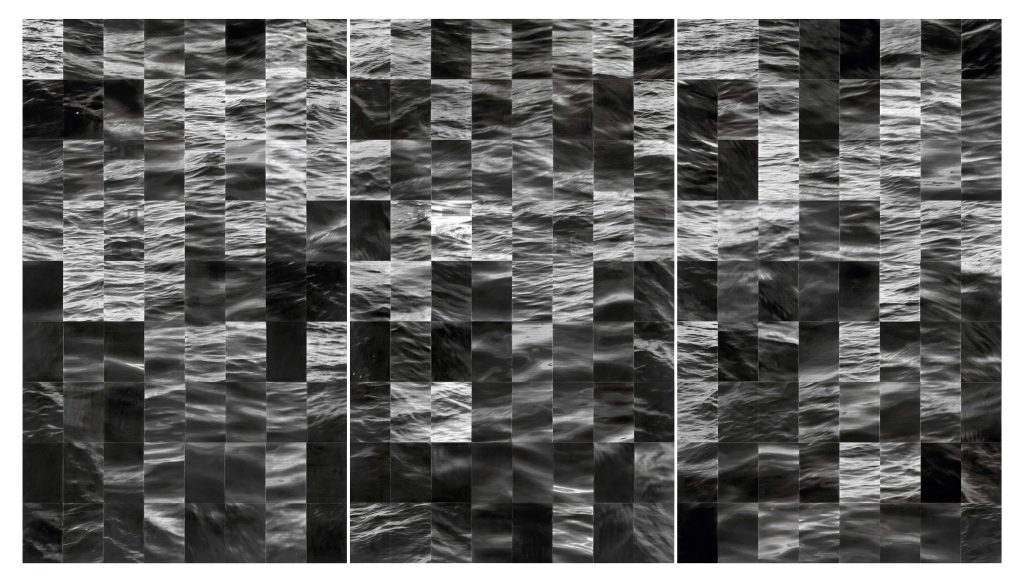

PF: In this exhibition, you present a quite large-scale work, Sea Surface – History of the World. In fact, this Sea Surface series comprises pieces such as Sea Surface – 1984, Sea Surface – Grimms’ Fairy Tales, Sea Surface – General History of China, and Sea Surface – Twenty-Four Histories. Can you share with us the inspiration and thoughts behind this series?

Li Shun: I grew up with a fascination for historical stories and a special curiosity about the sea. In 2017, I participated in a nautical artist residency project, where I spent three days and two nights on a sailing boat. During this immersive experience, I gazed at the sea for a long time, making me realize that the sea surface we see is in a perpetual state of change and circulation. Each wave is merely a fragment of the cyclical movement, just as the history we know is only a fraction of what really happened.

© Li Shun, Sea Surface- History of the World (exhibition view), 2023. Courtesy of Ginkgo Space

© Li Shun, Sea Surface- History of the World (detail), 2023.

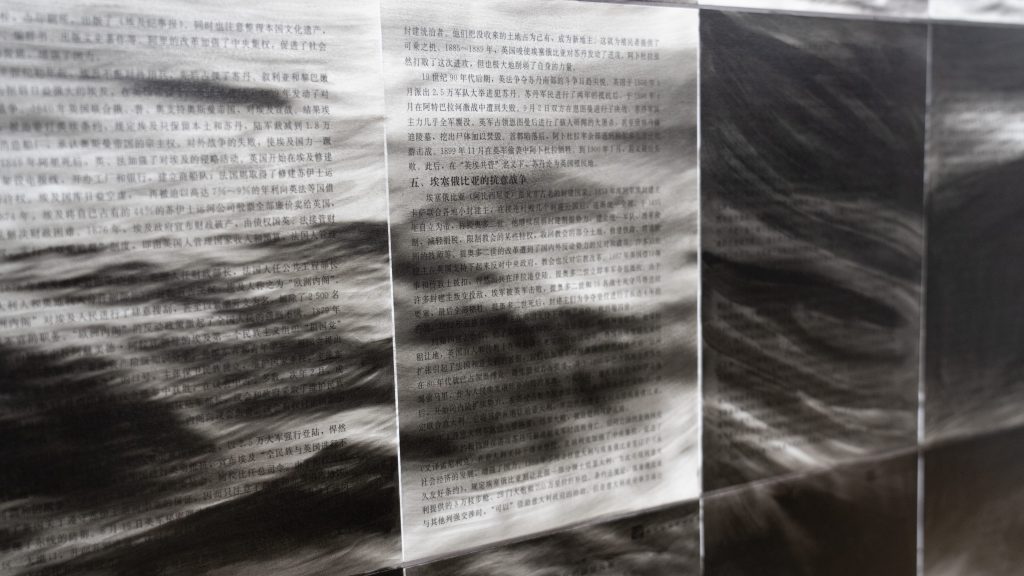

For Sea Surface – History of the World, I gathered various sea images from the internet and painted 864 sections of sea surfaces in an oil painting style directly on the pages of the history textbook, History of the World. The underlying concept revolves around the sea. The sea has no boundaries or emotions. It connects the whole world while maintaining mystery. The sea persists throughout time. Perhaps this is why I chose to paint it over the history written by humans. History is now concealed in the deepest shadows, forever beyond reach.

Also, the action of painting is an act of “covering.” The paintings on the book pages represent both a process of rewriting and covering. Paintings inherently carry human consciousness and emotions, just like how history is always intertwined with human perspectives. And the overlaying of perspectives leads to historical biases. Thus, the layered obscurity becomes an intriguing highlight of this series.

© Li Shun, Sea Surface- History of the World (detail), 2023.

PF: How do you interpret the concept of “copy”? And what is your understanding of the relationship between “truth” and “fiction”?

Li Shun: I’ve just looked into it, and a “copy” refers to a version other than the original—the opposite of the real deal. It’s an unofficial document. So, as you can see, it’s pretty easy to alter. In terms of history, people’s perspectives depend on which side of history they choose to embrace. Everyone stitches pieces of history together into their perception, and the same goes for their memories. Personally, I feel like this world is, in essence, virtual.

PF: How do we understand the roles of other art and literary works featured in your creations, and what significance do they carry?

Li Shun: Everyone’s outlook on history and the world is shaped by all kinds of texts. It depends on what they read about the Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, or the periods of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States, or the times of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors. So, their perspectives on history depend on which side of history they choose to embrace. Everyone stitches pieces of history together, but these are merely fragments. Some of them are the truth, some are just wrong, and some may seem beautiful and exciting yet fictional. Getting to understand the reasons behind those fictional histories reveals intriguing aspects. People learn about history through various means, often relying on history textbooks, myths, poetry, novels, or films. What I want to say is that, since history carries biases in different narrators’ accounts, I went for some widely acknowledged narration in my creations. Thus, I selected those literary works and transformed them into a form similar to their original state.

© Li Shun, Study on the nature of things - The General Pei's Poem, Photography, printed on rice paper, 180 x 337 cm, 3+1AP, 2023.

© Li Shun, Study on the nature of things - The General Pei's Poem (detail), 2023.

PF: How do you interpret the title of this exhibition, Stream of Ideas in Mountains and Seas? Compared to traditional Chinese landscape views, what do the natural landscapes in your works, such as mountains, seas, and the starry sky, symbolize?

Li Shun: The title suggests that the flow of ideas merges within the mountains and seas. In ancient China, literati expressed their sentiments through landscapes. Seeing Fan Kuan‘s Travelers Among Mountains and Streams from the Northern Song Dynasty, I can feel that “the universe is unkind; it regards everything as insignificant.” Human beings are like ants in front of the universe. But on the contrary, in the mundane world, what does the universe have to do with me? For ancient literati, landscape paintings were their expression of the universe. Similarly, in my works, the mountains and seas are the universe in my heart.

© Li Shun, Genesis - Brave New World, Oil on Novel Page, 45×60cm/ 60×80cm, Unique Edition, 2023.

PF: What aspects of Chinese traditional literati art captivate you the most? How do you perceive its relevance to its time?

Li Shun: Chinese traditional literati art, for me, embodies a spirit unbound by life rather than a mere inheritance of technical skills. Yet, for every Chinese person, regardless of whether they have experienced the cultural rupture of that era, tradition may shine through the cracks on us like sunlight—though not everyone chooses to explore those cracks. For example, in the Song and Yuan dynasties, the Eight Masters and Shi Tao are emblematic of their respective times.